This post is a part of my year-long quest in 2017 to read only female-authored travel writing. Find out more about it on the project’s main page.

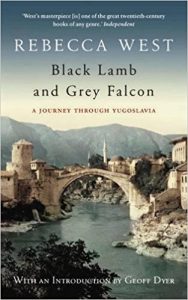

It’s more than a year after I published part one of my review of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon as part of my Reading Female Travel Writers project. As promised in that first part, I continued reading BL&GF, and in a sense I am not surprised it has taken me until now to finish it.

It is, as you’ll recall, an absolute window smasher of a tome, weighing in at 1100 pages (excluding preface and index), and I only got through the first 300 pages or so before the end of my allotted month last year. I committed to finishing it, though, and it’s taken me most of 2018 (albeit as a less disciplined reader than before) to do so and write a further review.

And if I had to summarise this second part of the review briefly, it would be to say that my key observations from that first review remain steadfast. The first part I managed to read, featuring Croatia, was characterised by long historical narrative, some exuberant and imaginative reflections on the people she meets, a meticulously detailed description of her daily activities, and a wonderful, poetic portrait of the people and places she encounters.

Having finished the book, I have little new to add to that.

She goes on in her journey, for example, with a long and deep take on the history of the region. There are some strong features in this – her description of the events leading up to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand is intermittently gripping, and she writes poignantly about the devastation of war on the geography, culture and psyche of the region, not least the First World War. And you’re left with no doubt as to the rich, confusing and truly European flavour of Yugoslavia as a result of the multitude of interests (mostly malign) that have shaped it, such as Austria, Germany, Italy and of course the Ottoman Empire.

Similarly, my criticism in the first review also still stands, in that this history is at times far too lengthy and detailed for a travelogue, and as I continued with the book I confess the pace with which I began skim-reading those expositions, or indeed skipping them entirely, increased.

Indeed, the book concludes with what is supposed to be an explanation from West of why she so loves this part of the world and why she should labour so fervently to write this book (albeit the book itself should stand as the answer to this question). Yet this eighty page epilogue morphs carelessly into an unnecessary general meditation on the nature of empires, and an overview of the First World War which is not even particularly about the region’s important and tragic role within it.

But the book does linger in the mind, and does grab the attention from time to time with some sadly all too infrequent beauty and power. In between my bouts of skimming, I did genuinely enjoy reading more about the places I’d visited and have read so much about elsewhere, across the likes of Bosnia, Montenegro and Kosovo.

Macedonia is also a highlight, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, West’s love for the region shines through in the enthusiastic way she writes about it and even in the long, rambling historical expositions. The people, places and culture are written about passionately and fondly.

Secondly, there is some discomfort in the story for the author that presents some unintended comedy relief. Travelling with West and her husband throughout nearly the whole journey is their friend Constantine, a poet and journalist – and committed Serbian nationalist (West’s name for him is a pseudonym and you can read about the man himself, Stanislav Vinaver, on his very interesting Wikipedia page). His cultural insight, contacts, and of course native command of Serbo-Croat is an important part of the success of West’s journey and the depth of her understanding, and “Constantine” himself is portrayed with affection and respect, and comes over well.

But for a large part of the journey, including the chapter on Macedonia, his morose, negative and bitter German wife Gerda joins them. Her grumpiness, contrary nature and general unpleasantness brings down the mood to more than occasional humorous effect. West, intensely annoyed by Gerda’s presence, lets her frustration show in her lengthy diatribes about Gerda’s behaviour, the difficult position Constantine is put in, and the impact she has on the group atmosphere. I was thus disappointed when Gerda, who knew she was not appreciated by her fellow travellers, eventually stormed off home, leaving the party to be dominated once more by West’s seemingly endless thoughts.

I should draw this additional review to a close before I begin adopting some of West’s bad habits and waxing philosophically about matters that are only barely relevant to the topic.

I’m glad I’ve read the book, and genuinely glad I stuck at it when at times I was tempted to give up. It is, in most senses, a better book than the one in my project I did give up on: West is an intense, passionate and immensely intelligent and learned writer. She brings people and places to life with occasionally rich beauty, and the depth of research into the area she has undertaken is impressive.

Moreover, it was very interesting to read about the parts of the region I have visited and known, a familiarity keeping my attention to the details where otherwise it might not. Mind you, given that good travel writing should broaden the horizons and inspire you about places you don’t know, more than indulge your love of places you do, I am not sure that is a strong compliment to pay the book.

What it is, though, is probably the most helpful tip I can offer someone who might be considering picking up BL&GF and scaling the daunting peaks of its thousand or so pages. The book is undoubtedly an important piece of twentieth century travel writing, and an especially noteworthy one if looking, as I did last year, at female travel writing.

But I couldn’t honestly commend it to someone with no interest in Yugoslavia, and to those who do have a passion for the region I would suggest starting with the introduction and then not feeling at all guilty for taking a non-linear approach to the mostly self-contained chapters. I would recommend jumping to the areas you yourself know best. That familiarity will be an anchor through the tough treacle of West’s narrative, and if you survive that and are hungry for more, then godspeed and good luck but don’t feel bad if, like me, you find yourself skimming and skipping, and certainly don’t beat yourself up if you don’t finish it.

I feel bad ending my very last piece of content on my year-long reading mission on such a negative tone when I enjoyed the broader mission so much. West was clearly a remarkable woman and BL&GF is an impressive piece of writing. But if you wish to be inspired by the works of female travel writers or, like me at the start of the mission, you’ve read none, then many others on my list would be much stronger recommendations.

See my full reading list with links to previews and reviews on the project’s main page, and might I suggest you finish on a much more positive note by reading my post about the conclusions I can draw from a year of reading female travel writers.