This post is a part of my year-long quest in 2017 to read only female-authored travel writing. Find out more about it on the project’s main page.

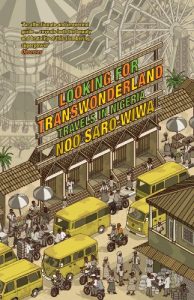

Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria by Noo Saro-Wiwa is the second book I have included in this series which is by a black woman. Like the other, last month’s Tell My Horse, I discovered it in this article by American writer Nneka Okona about black female travel writers.

Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria by Noo Saro-Wiwa is the second book I have included in this series which is by a black woman. Like the other, last month’s Tell My Horse, I discovered it in this article by American writer Nneka Okona about black female travel writers.

I explain more in my preview of Tell My Horse about my rationale for wanting to include some racial diversity, so those general points in that review relate to this one too.

Three things specifically drew me to this book however. The first was the fact that the subject in question is in Africa, a continent I’ve yet to visit in this reading mission (except for the occasional fleeting trip in January’s anthology).

Also, Nigeria is not on my radar particularly, and the cliches I hear – the violence, the poverty, the corruption – are probably excruciating to anyone who knows and loves it, and doubtless (even if based on some truth) only a tiny part of what makes the country what it is. And if this mission should help me to do anything, it should help me to overcome some stereotypes.

The final wee detail that stuck out to me was the author’s name, Noo Saro-Wiwa. It rang vague bells in my head because she is the daughter of Ken Saro-Wiwa, a political activist who was executed by the Nigerian government in the 1990s for his campaigning against the environmental exploitation of his region by the country’s oil industry.

Noo Saro-Wiwa, as she explains in the beautifully written prologue, was born in Nigeria but moved to England as a baby with her family, and although she grew up in the UK she had regular childhood trips back to her family’s home in Nigeria.

These were not always enjoyable trips for her as a British child brought up with European comforts, and having to cope with trips to a land of mosquitoes and carrying your own water and not quite understanding the language of the extended family. She sets the scene passionately but breezily in her prologue about “my unglamorous, godforsaken motherland with its penchant for noise and disorder” where the “humid viscous air, pointlessly stirred by sleepy ceiling fans, would smother me like a pillow and gave a foretaste of the decrepitude and discomfort that lay ahead”.

Her reluctance to embrace Nigeria is exacerbated when she discovers she has half-siblings over there, from her father’s polygamy. “He called it tradition. I took it as a betrayal”.

It is only upon her father’s death, her adulthood, her travels around the world for her work, and the fact she is no longer forced to go there that she decides she must reappraise Nigeria. It was a country that was (as she powerfully puts it) an “unpiloted juggernaut of pain [which] became the repository for all my fears and disappointments; a place where nightmares did come true.” Determined to try to get beyond that image of the country, she heads off.

It’s a packed and revealing prologue in which we learn much about her, her father, and indeed her experience of Nigeria. If the book wasn’t appealing before getting stuck in, the opening certainly serves that purpose, and I feel fully dragged in and eager to continue.

Saro-Wiwa’s pace is energetic and her writing is powerful and poetic, so I think I am in for a dramatic and emotional ride this month. We’ll see. As usual, my review will follow at the end of the month.