This post is a part of my year-long quest in 2017 to read only female-authored travel writing. Find out more about it on the project’s main page.

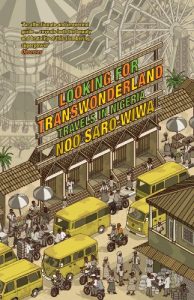

I really enjoyed Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria by Noo Saro-Wiwa, for a few reasons.

I really enjoyed Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria by Noo Saro-Wiwa, for a few reasons.

Firstly, as I completed November’s title in my reading series, I realised I had now only one book to go before the mission was over and I could reflect on the many things I have taken from it (and I will write a big post-mission reflection in the new year).

Secondly, I appreciated the challenge of a very different perspective in my second of two books by non-white authors (and read October’s preview for an explanation of how I ended up choosing this book and last month’s Tell My Horse). And that’s a wee hint about one of my learning points you’ll read about in that big post-mission reflection.

Thirdly, and most importantly, Looking for Transwonderland is a superb piece of travel writing. Noo Saro-Wiwa’s journey around her country of origin is beautifully written, revealing, emotional, evocative, entertaining and more than occasionally amusing.

As I explained in the preview, Looking for Transwonderland is the author’s attempt to discover more about the country she was born in and regularly visited as a child, and in doing so to see it through her own eyes as an adult and move beyond the prism of the influence of her late father, the executed political activist Ken Saro-Wiwa.

That straight away presents an intimacy to the reader: this isn’t a book by a dispassionate author, helping us to appreciate a strange place by showing us how strange it also is to them. This is an author who is travelling a country she knows well in some senses. And, on reflection, I don’t think I’ve read too many books by those with such a deep personal connection.

On a practical level this means the author interacts with more local people than we might often read about in a typical travelogue – including family members, acquaintances of her father or even people who know his name and have a forthright opinion about his legacy. And that is rewarding in itself.

But on a creative level, her connection to the country creates a richer and more powerful narrative, a prose that brims with emotion and urgency, and a passion for what she encounters that is infectious.

Mind you, that passion doesn’t translate for me into an instant desire to hop on a plane to Nigeria, and I doubt it will for many European readers. The author does not hold back on presenting the (many) negative sides of the country, and although she is not unnecessarily unkind to the country and does have many positive experiences, she is open and honest in sharing her dislikes about the place – stretching back as they do to her childhood. Reflecting early on in the book on her childhood visits, for example. she writes:

As a teenager, I virtually had to be escorted by the ankles onto a Nigeria Airways flight at the start of the holidays, not only because I wanted to avoid all that airport angst, but also because i didn’t want to reach the ultimate destination. Having to spend those two months in my unglamourous, godforsaken motherland with its penchant for noise and disorder felt like a punishment… I would arrive at an airport that hadn’t been refurbished in twenty years. The humid viscous air, pointlessly stirred by sleeping ceiling fans, would smother me like a pillow and gave a foretaste of the decrepitude and discomfort that lay ahead.

And she describes Nigeria as

an unpiloted juggernaut of pain, and it became the repository for all my fears and disappointments

Though in a sense it was that tortured view of the country, an experience exacerbated by the fact that it was the place whose government killed her father, that drove her to try to reappraise the country with fresh, adult eyes. As she says herself,

Nigeria began to take on a certain mystique, especially as I was no longer forced to spend time there.

And in this we have one of the book’s major ongoing themes, Saro-Wiwa’s role as both insider and outsider. Although she has a familiarity with the places and people she encounters, she is angry at the poverty, crime, corruption and dirt she sees everywhere, is easily recognised as a foreigner by most strangers, and at time struggles with the heat, exhaustion, decrepit infrastructure and consistently dreadful customer service. Yet she nearly always talks about the Nigerian people as “we”, and exudes affection for the country in the strangest of circumstances.

She writes at one point when in the largest city, Lagos, about the country’s endemic corruption:

No facet of the economy goes unaffected: every road, school, oil drum, hospital or vaccine shipment is milked for cash. It diminishes the quality and quantity of everything in the country, including our self-esteem. For it doesn’t matter what I might achieve in life, these street scenes represent me… The world judges me according to this mess, and looking at it made me feel rather worthless.

This is mirrored in her itinerary. She visits familiar places, even her old family home, catches up on relatives she’s not seen for years, and retraces her steps of trips she was taken on by her father. Yet she goes beyond her old stomping grounds in a sweeping circuit of the country that takes in the full ethnic, cultural, geographical and environmental diversity of what is, after all, a huge and varied land.

And while the insider hat gives her insight and connection, it’s often when she has the outsider hat on that the writing becomes most powerful. As a fresh pair of eyes, seeing things in the country either for the first time or the first time in years, she’s able to write openly and uncompromisingly.

The poverty, for example, hits her hard. In chaotic, overcrowded Lagos, for instance,

At a glance, the insouciant muscularity of the beggars’ bodies masks the ravages of regularly skipped meals, not to mention tooth decay, depression, dulled IQs and parasitic infections. Often illiterate, these people are deaf to the city’s posters and billboards that speak endlessly of God’s love for them. One in five of the barefoot toddlers defecating on the roadsides won’t live long enough to start primary school. Their births and deaths are not registered in any formal sense. They enter and exit the world unnoticed by government, with few photographs to commemorate their brief existence. Forced to live like animals yet cursed with the fears of human consciousness, the plight of these Nigerians made me question not just the purpose of life, but the very point of it.

There’s sometimes time for humour in the chaos, though:

Nigerians love to transform every place into a giant market, no matter how grand the location. We’ll grab any opportunity to sell, discarding all sense of pomp and ceremony. If Nigeria conducted a space exploration programme, you know that women would be offering bananas to the astronauts as they climbed aboard the shuttle.

And she admirably finds the positive in the country where, perhaps, a white European travel writer might struggle to do so:

Lagos had taken me through many emotions that day. I was feeling particularly chastened and disorientated, but at least boredom hadn’t come into it: for all its defects the city never failed to deliver buttock-clenching excitement, and I was grateful for that.

Saro-Wiwa also introduces some fascinating aspects to the country that I’d certainly never heard of, that help the reader get beyond the cliches and headlines of violence, oil and corruption. I suspect I am not the only one to be surprised to learn that, for instance, Lagos boasts some colonial Portuguese influence in its architecture, thanks to ethnic Nigerians, descendents of slaves, returning to their mother country in the nineteeth century from Brazil. We also meet evicted white Zimbabwean farmers have been setting up new lives and transforming agriculture in Nigeria; and we encounter the notable and quite wealthy Lebanese population in the country.

Regarding the latter, a moment in the book presents both a snapshot of this and the author’s skill in capturing it:

As the Lebanese men played football on the beach, a Nigerian hawker stood nearby and watched them, a tray of fruit balanced on top of his head. I couldn’t tell if he was waiting to sell them something, or whether he was simply fixated by the game; either way, he cut a frustratingly marginalised, shabby figure against their flabby affluence.

And elsewhere, she talks about the country’s beautiful countryside and rich cultural history (albeit both poorly protected), the phenomenon that is Nollywood, and the huge role that religion plays. She wittily remarks about the Christian part of the country’s fervour in prayer, in a joke I think it takes a Nigerian to have the confidence to make:

According to the Bible, God made the earth in six days and took a rest on the seventh. But by creating Nigerians, he ensured that that was the last day off he’s enjoyed ever since.

And one highlight for me is a visit Saro-Wiwa makes to an amusement park, Transwonderland, from where she gets the book’s title. The crumbling, poorly-maintained park forms a sobering metaphor for the state of the entire country, the author writing:

As the manager repeatedly stepped onto the platform to push the cars along, I wondered why nothing ever lasts in Nigeria, and how institutions like Transwonderland kept going long after their economic viability had expired, like twitching corpses that refuse to die.

Although the author defines herself by her Nigerian roots but British upbringing, her gender does come into play now and then. She talks about the inherent misogyny in many parts of Nigerian society, though she reflects on her own gender only rarely. In the face of so much sexism and danger to personal security I found that surprising; though the author was streetwise and well-informed by locals, which doubtless helped.

In conclusion, it was a privilege to join Noo Saro-Wiwa on her very personal pilgrimage. Reading the thoughts of a Londoner returning to her African mother country to reflect on her place within it was an unusual experience for me, and one that provided me with some significant insight into the role of identity in travel. While, as I say, gender did not dominate the book as a theme, it certainly played an important role in the author’s distinct voice and her passionate, beautiful and authoritative writing.

While I found the reflections on the desperately sad state Nigeria finds itself in to be unrelentingly depressing and heartbreaking – and for that reason it is not an easy read at times – the author finds enough chinks of light in this to hold some slight optimism for the country, and (re?)gain not a little love for it. Looking for Transwonderland is a powerful book, and a gripping, informative and well-written one. It has wowed me and depressed me in equal measure, a contradiction that – like the author’s perspective as both insider and outsider – is a strength much more than a flaw.